China's 'Special Port Fee' on U.S.-Linked Vessels: The Logic Behind the Countermeasure

Following the recent revision of the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on International Ocean Shipping—which created a legal basis for countermeasures against the U.S. Section 301 investigation into China’s maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding industries—China has now moved from preparation to action.

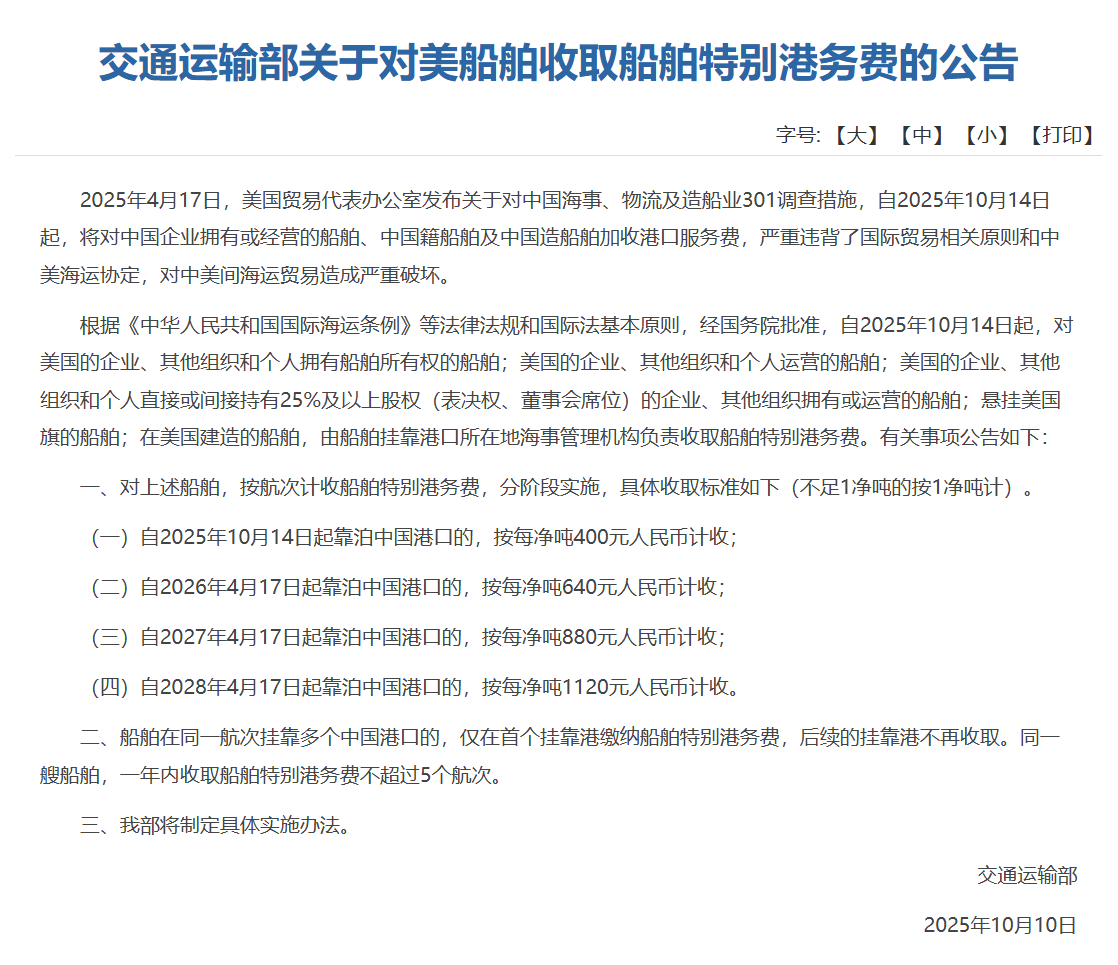

On October 10, China's Ministry of Transport announced that, effective October 14, 2025, all U.S.-related vessels will be subject to a new "Special Port Fee", a reciprocal response to what China calls discriminatory and protectionist U.S. port charges imposed under the 301 framework.

The real significance lies in the scope of what constitutes a "U.S.-related vessel." The definition extends far beyond ships built or flagged in the United States, to include vessels owned, operated, or indirectly controlled by U.S. companies, citizens, or investors.

This encompasses fleets owned by U.S.-listed shipping firms, energy majors, traders, investment funds, and banks, which together represent a substantial share of the global fleet. In other words, although the number of U.S.-flag or U.S.-built merchant ships is relatively small, U.S. capital influence in world shipping is immense.

The decision is therefore not symbolic—it targets a large and globally dispersed network of U.S.-linked maritime assets.

The move marks the start of a new phase in the U.S.–China maritime policy standoff, highlighting the extensive footprint of American interests in international shipping.

Countering the Section 301 Tariffs — "Legal and Lawful Defense"

On April 17, 2025, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) concluded the Section 301 investigation into China's maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding sectors, announcing that, effective October 14, it would levy port service fees on Chinese-owned, Chinese-operated, and China-built vessels.

The measure was widely viewed as a violation of both international trade principles and the U.S.–China Maritime Agreement, carrying clear elements of discrimination and protectionism.

China’s Ministry of Transport stated that its countermeasure aims to safeguard the legitimate interests of Chinese shipping companies and level the playing field in the maritime market. With approval from the State Council, the ministry invoked domestic law and international legal principles to enact this reciprocal measure.

Scope and Implementation

According to the official circular, the "Special Port Fee" applies to any vessel that meets one or more of the following criteria:

- Owned by U.S. companies, organizations, or individuals;

- Operated by U.S. companies, organizations, or individuals;

- Owned or operated by an entity in which U.S. companies, organizations, or individuals directly or indirectly hold 25% or more of equity, voting rights, or board - seats;

- Registered under the U.S. flag;

- Built in the United States.

*Detailed implementation guidelines will follow.

Following the recent revision of the Regulations of the People's Republic of China on International Ocean Shipping—which created a legal basis for countermeasures against the U.S. Section 301 investigation into China’s maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding industries—China has now moved from preparation to action.

On October 10, China's Ministry of Transport announced that, effective October 14, 2025, all U.S.-related vessels will be subject to a new "Special Port Fee", a reciprocal response to what China calls discriminatory and protectionist U.S. port charges imposed under the 301 framework.

The real significance lies in the scope of what constitutes a "U.S.-related vessel." The definition extends far beyond ships built or flagged in the United States, to include vessels owned, operated, or indirectly controlled by U.S. companies, citizens, or investors.

This encompasses fleets owned by U.S.-listed shipping firms, energy majors, traders, investment funds, and banks, which together represent a substantial share of the global fleet. In other words, although the number of U.S.-flag or U.S.-built merchant ships is relatively small, U.S. capital influence in world shipping is immense.

The decision is therefore not symbolic—it targets a large and globally dispersed network of U.S.-linked maritime assets.

The move marks the start of a new phase in the U.S.–China maritime policy standoff, highlighting the extensive footprint of American interests in international shipping.

Countering the Section 301 Tariffs — "Legal and Lawful Defense"

On April 17, 2025, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) concluded the Section 301 investigation into China's maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding sectors, announcing that, effective October 14, it would levy port service fees on Chinese-owned, Chinese-operated, and China-built vessels.

The measure was widely viewed as a violation of both international trade principles and the U.S.–China Maritime Agreement, carrying clear elements of discrimination and protectionism.

China’s Ministry of Transport stated that its countermeasure aims to safeguard the legitimate interests of Chinese shipping companies and level the playing field in the maritime market. With approval from the State Council, the ministry invoked domestic law and international legal principles to enact this reciprocal measure.

Scope and Implementation

According to the official circular, the "Special Port Fee" applies to any vessel that meets one or more of the following criteria:

- Owned by U.S. companies, organizations, or individuals;

- Operated by U.S. companies, organizations, or individuals;

- Owned or operated by an entity in which U.S. companies, organizations, or individuals directly or indirectly hold 25% or more of equity, voting rights, or board - seats;

- Registered under the U.S. flag;

- Built in the United States.

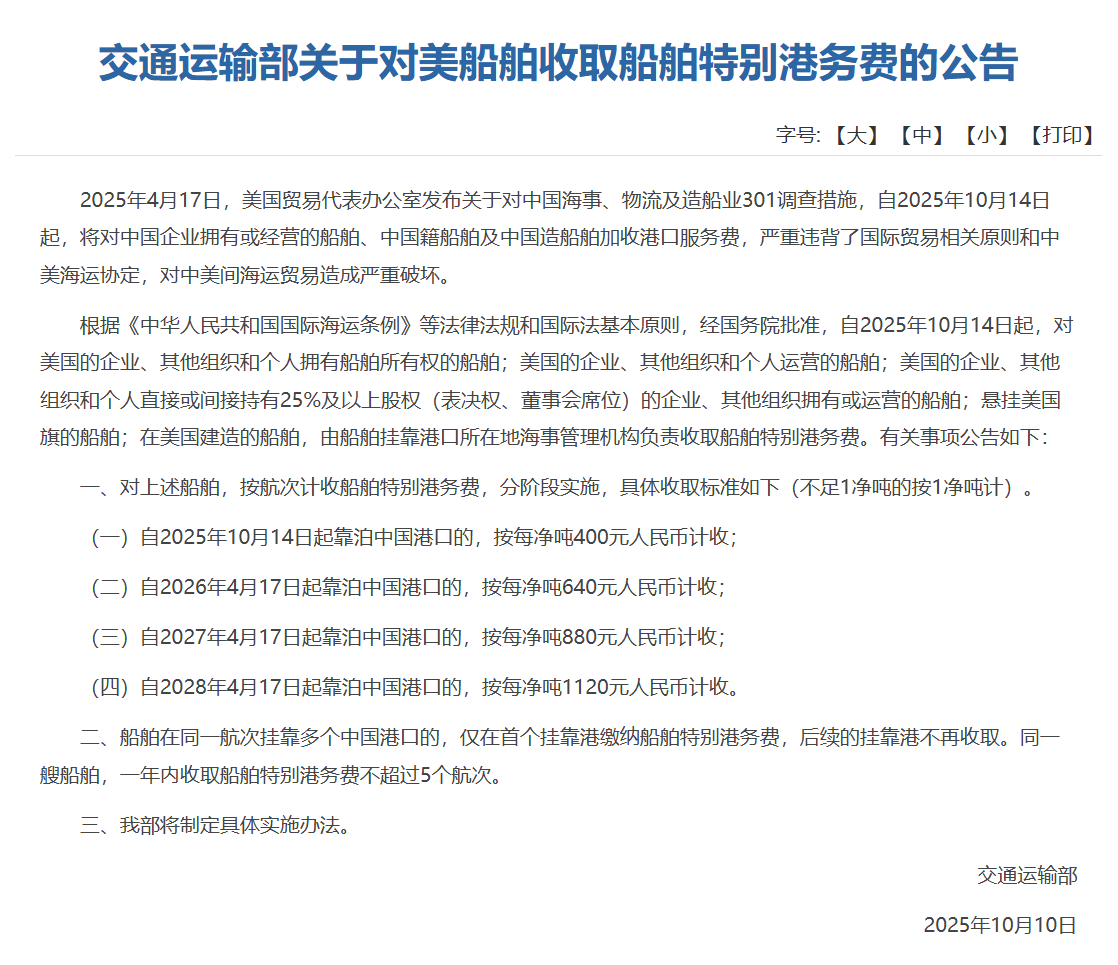

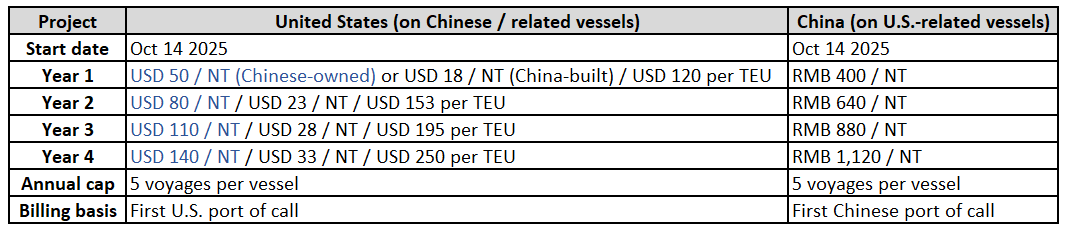

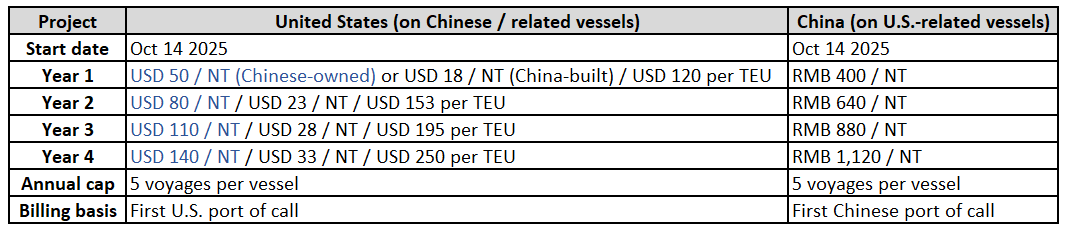

The fee is collected per voyage by the maritime authority at the vessel’s first Chinese port of call. If a voyage calls at multiple Chinese ports, it is paid once only; no more than five voyages per vessel per year will be charged.

| Effective Date | Fee (RMB / Net Ton) |

| Oct 14 2025 | CNY 400 |

| Apr 17 2026 | CNY 640 |

| Apr 17 2027 | CNY 880 |

| Apr 17 2028 | CNY 1,120 |

A Symmetrical and Measured Response

The structure of China's fee closely mirrors the U.S. fee schedule in both its phased implementation and the magnitude of charges.

The structure of China's fee closely mirrors the U.S. fee schedule in both its phased implementation and the magnitude of charges.

From the author's perspective, China's response strikes a balance between reciprocity and restraint. From its legal foundation to its phased implementation schedule, the policy demonstrates a measured and rules-based logic.

By contrast, the U.S. Section 301 measures include additional charges and restrictions specifically targeting certain ship types. Under Annex III, effective October 14, 2025, all non-U.S.-built vehicle carriers will be subject to a port service fee of USD 150 per car unit (CEU) — a move intended to pressure global operators to order U.S.-built replacements. Annex IV, meanwhile, introduces from 2028 onward a build-origin restriction on LNG carriers used for U.S. LNG exports, requiring that over the next 22 years at least 15% of exported LNG cargoes be carried by U.S.-built, U.S.-flagged, and U.S.-operated vessels, effectively reshaping the U.S. LNG fleet toward localization.

In contrast, China's Special Port Fee applies no such industrial or vessel-specific conditions. It does not target particular ship types such as vehicle carriers or LNG carriers, nor does it include any domestic-build requirement or policy linkage. Instead, the measure is entirely based on reciprocal legal grounds, defined by a vessel's ownership, operation, flag, or level of U.S. equity control. This reflects a clearer sense of legal symmetry and institutional restraint, rather than an orientation toward industrial protectionism or market exclusion.

Furthermore, China's definition of "U.S.-related vessels" directly mirrors the U.S. definition of "Chinese-related vessels" set out in the earlier Section 301 documentation—without expansion or reinterpretation.

The underlying intent is to safeguard fairness for Chinese shipping through a rule-based and institutionalized approach, aiming to steer global maritime governance back toward reason and dialogue.

As the Ministry of Transport noted in its press briefing:

"The U.S. measure disregards facts and exposes its unilateral and protectionist nature. It seriously undermines the legitimate interests of China's maritime sector and disrupts global supply-chain stability. China's countermeasure is a lawful act to protect the legitimate rights of its shipping companies."

Ultimately, the approach reflects the belief that cooperation benefits both sides, while confrontation harms both. The policy signals China's intent to counter unilateralism with rules and respond to pressure with rationality—asserting national interests firmly, yet avoiding escalation. The aim is to use reciprocity to restore balance, encouraging both sides to return to the negotiating table.

How Many "U.S.-Linked Vessels" Are There?

Following the announcement, some observers questioned the practical impact of the countermeasure, citing the limited number of U.S.-built or U.S.-flagged commercial ships. However, the regulation's broad definition paints a different picture.

According to VesselsValue, the United States ranks as the world’s fourth-largest ship-owning nation by fleet value as of January 2025, covering bulk carriers, tankers, gas carriers, and container ships.

Another question concerns whether shipping companies listed in the United States—and the fleets they own or operate—will be regarded as "U.S.-related vessels."

The announcement issued on October 10 was concise, and several aspects remain open to clarification. The Ministry of Transport noted that detailed implementation measures will be formulated in due course.

The True Scale of "U.S.-Related Fleets" May Be Much Larger

As previously noted, VesselsValue data show that the United States ranks as the world's fourth-largest shipowning nation, with extensive holdings in dry bulk, tanker, gas carrier, and container tonnage.

When one considers the criteria of ownership, operation, or direct or indirect U.S. equity participation exceeding 25 percent of voting rights or board seats, the total number of vessels potentially falling under the "U.S.-related" category could be significantly higher.

From the ownership perspective, the United States has applied similar criteria in its own 301-related definitions of "Chinese-owned vessels." Under those U.S. rules, any owning entity incorporated in mainland China, Hong Kong, or Macao is considered a Chinese shipowner. The same applies if the entity’s parent company, headquarters, or principal place of business is located in one of those regions.

Additionally, if 25% or more of a company’s issued voting rights, board seats, or equity are directly or indirectly held by Chinese interests, that company is also deemed Chinese-owned.

China’s regulation follows an analogous logic. However, questions remain over how "U.S. companies and other organizations" will be interpreted in practice—specifically regarding registration, principal place of business, or headquarters location.

There is also uncertainty over whether U.S. unincorporated territories such as Puerto Rico, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Palmyra Atoll, American Samoa, Midway, Wake, Navassa, Baker, Howland, Jarvis, and Johnston Atoll will be treated similarly to Hong Kong or Macao under the new rules.

Likewise, the inclusion of U.S.-listed shipping companies and their fleets awaits further clarification.

According to data compiled by Xinde Marine News, shipping companies listed in the United States include (but are not limited to):

Star Bulk Carriers (SBLK), Genco Shipping & Trading (GNK), Eagle Bulk Shipping (EGLE, pending merger with Star Bulk), Golden Ocean Group (GOGL), Diana Shipping (DSX), Safe Bulkers (SB), Navios Maritime Holdings (NM), Navios Maritime Partners (NMM), Seanergy Maritime (SHIP), Castor Maritime (CTRM), Scorpio Tankers (STNG), Euronav (EURN), Frontline (FRO), International Seaways (INSW), DHT Holdings (DHT), Nordic American Tankers (NAT), Teekay Tankers (TNK), Overseas Shipholding Group (OSG), Tsakos Energy Navigation (TNP), Dorian LPG (LPG), Flex LNG (FLNG), Golar LNG (GLNG), Capital Product Partners (CPLP), ZIM Integrated Shipping Services (ZIM), Matson (MATX), Costamare (CMRE), and Kirby Corporation (KEX).

While some—such as Matson and OSG—are purely American companies, many others are controlled by Greek, Norwegian, or Israeli shipowners and operate large, internationally financed fleets. Collectively, these U.S.-listed firms control or operate thousands of vessels across all major sectors.

U.S. financial institutions, including Citigroup, J.P. Morgan, Oaktree Capital, and BlackRock, also manage or invest in significant port and fleet assets through leasing or capital investment structures.

If China adopts an operational definition of “operator” similar to that used in the U.S. Section 301 framework, the scope could expand even further. Many non-U.S.-flagged or non-U.S.-built vessels chartered on voyage, time, or bareboat terms by U.S. companies would likely fall within this category.

In addition to the listed shipping firms, major energy companies such as ExxonMobil, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips, as well as commodity traders like Cargill, ADM, and Bunge, operate substantial chartered fleets. Cargill Ocean Transportation, for example, manages a charter fleet exceeding 650 vessels worldwide.

TradeWinds data show that in most publicly listed shipping companies, U.S. investors hold more than 25 percent of equity, surpassing the ownership threshold defined under China's forthcoming measure.

Given that China is the world’s largest manufacturing and trading nation—and home to the busiest port network—virtually every major vessel type must regularly call at Chinese ports. This means the potential reach of the "Special Port Fee" could extend far beyond what headline figures on U.S.-flag tonnage might suggest.

Compared with the U.S. regime, China’s forthcoming measure could affect a broader and more diverse range of shipowners. Some external commentators have argued that China "has no meaningful card to play" or that the measure is "not truly reciprocal," but such assessments appear to underestimate both China's market leverage and its regulatory sophistication.

In reality, China is the world's largest manufacturer, top exporter, and a critical hub of global shipping demand. Almost all major ocean carriers, operators, and charterers—regardless of nationality—depend on access to Chinese ports. As such, any institutional adjustment introduced by China carries significant global implications.

China’s Position: Rational Counteraction, Stability Through Dialogue

As previously discussed, China's response represents reciprocal counteraction tempered by restraint. Facing what it views as a politicized and discriminatory Section 301 measure, China has chosen to respond with law, not retaliation, reflecting both governance maturity and strategic confidence.

The "Special Port Fee" is not an emotional reaction but a structured, rule-based response. From its timeline and fee schedule to its eligibility criteria and review cycle, the measure is designed with symmetry and transparency, signaling both a firm rejection of unequal treatment and a willingness to maintain dialogue.

In a world of deeply interconnected supply chains, stability outweighs confrontation. The purpose of countermeasures is to uphold legality, not to escalate; restraint serves to preserve rationality, not to concede. By responding to rules with rules and balancing institutions with institutions, China seeks to promote a fair, cooperative, and rules-based maritime order.

This transcends a mere dispute over port fees—it signifies a broader rebalancing of fairness, governance, and influence in global maritime affairs. Through a policy of rational counteraction and stability-driven engagement, China aims to demonstrate the posture of a responsible maritime power: firm, composed, and predictable.

As a Ministry of Commerce spokesperson put it, the countermeasure "aims to safeguard fair competition in the international shipping and shipbuilding markets" and constitutes "a legitimate act of legitimate defensive measure." The spokesperson added that China hopes the United States "will reconsider, correct its mistake, and work toward constructive solutions through equal consultation and cooperation."

by Xinde Marine News Chen Yang

By contrast, the U.S. Section 301 measures include additional charges and restrictions specifically targeting certain ship types. Under Annex III, effective October 14, 2025, all non-U.S.-built vehicle carriers will be subject to a port service fee of USD 150 per car unit (CEU) — a move intended to pressure global operators to order U.S.-built replacements. Annex IV, meanwhile, introduces from 2028 onward a build-origin restriction on LNG carriers used for U.S. LNG exports, requiring that over the next 22 years at least 15% of exported LNG cargoes be carried by U.S.-built, U.S.-flagged, and U.S.-operated vessels, effectively reshaping the U.S. LNG fleet toward localization.

In contrast, China's Special Port Fee applies no such industrial or vessel-specific conditions. It does not target particular ship types such as vehicle carriers or LNG carriers, nor does it include any domestic-build requirement or policy linkage. Instead, the measure is entirely based on reciprocal legal grounds, defined by a vessel's ownership, operation, flag, or level of U.S. equity control. This reflects a clearer sense of legal symmetry and institutional restraint, rather than an orientation toward industrial protectionism or market exclusion.

Furthermore, China's definition of "U.S.-related vessels" directly mirrors the U.S. definition of "Chinese-related vessels" set out in the earlier Section 301 documentation—without expansion or reinterpretation.

The underlying intent is to safeguard fairness for Chinese shipping through a rule-based and institutionalized approach, aiming to steer global maritime governance back toward reason and dialogue.

As the Ministry of Transport noted in its press briefing:

"The U.S. measure disregards facts and exposes its unilateral and protectionist nature. It seriously undermines the legitimate interests of China's maritime sector and disrupts global supply-chain stability. China's countermeasure is a lawful act to protect the legitimate rights of its shipping companies."

Ultimately, the approach reflects the belief that cooperation benefits both sides, while confrontation harms both. The policy signals China's intent to counter unilateralism with rules and respond to pressure with rationality—asserting national interests firmly, yet avoiding escalation. The aim is to use reciprocity to restore balance, encouraging both sides to return to the negotiating table.

How Many "U.S.-Linked Vessels" Are There?

Following the announcement, some observers questioned the practical impact of the countermeasure, citing the limited number of U.S.-built or U.S.-flagged commercial ships. However, the regulation's broad definition paints a different picture.

According to VesselsValue, the United States ranks as the world’s fourth-largest ship-owning nation by fleet value as of January 2025, covering bulk carriers, tankers, gas carriers, and container ships.

Another question concerns whether shipping companies listed in the United States—and the fleets they own or operate—will be regarded as "U.S.-related vessels."

The announcement issued on October 10 was concise, and several aspects remain open to clarification. The Ministry of Transport noted that detailed implementation measures will be formulated in due course.

The True Scale of "U.S.-Related Fleets" May Be Much Larger

As previously noted, VesselsValue data show that the United States ranks as the world's fourth-largest shipowning nation, with extensive holdings in dry bulk, tanker, gas carrier, and container tonnage.

When one considers the criteria of ownership, operation, or direct or indirect U.S. equity participation exceeding 25 percent of voting rights or board seats, the total number of vessels potentially falling under the "U.S.-related" category could be significantly higher.

From the ownership perspective, the United States has applied similar criteria in its own 301-related definitions of "Chinese-owned vessels." Under those U.S. rules, any owning entity incorporated in mainland China, Hong Kong, or Macao is considered a Chinese shipowner. The same applies if the entity’s parent company, headquarters, or principal place of business is located in one of those regions.

Additionally, if 25% or more of a company’s issued voting rights, board seats, or equity are directly or indirectly held by Chinese interests, that company is also deemed Chinese-owned.

China’s regulation follows an analogous logic. However, questions remain over how "U.S. companies and other organizations" will be interpreted in practice—specifically regarding registration, principal place of business, or headquarters location.

There is also uncertainty over whether U.S. unincorporated territories such as Puerto Rico, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Palmyra Atoll, American Samoa, Midway, Wake, Navassa, Baker, Howland, Jarvis, and Johnston Atoll will be treated similarly to Hong Kong or Macao under the new rules.

Likewise, the inclusion of U.S.-listed shipping companies and their fleets awaits further clarification.

According to data compiled by Xinde Marine News, shipping companies listed in the United States include (but are not limited to):

Star Bulk Carriers (SBLK), Genco Shipping & Trading (GNK), Eagle Bulk Shipping (EGLE, pending merger with Star Bulk), Golden Ocean Group (GOGL), Diana Shipping (DSX), Safe Bulkers (SB), Navios Maritime Holdings (NM), Navios Maritime Partners (NMM), Seanergy Maritime (SHIP), Castor Maritime (CTRM), Scorpio Tankers (STNG), Euronav (EURN), Frontline (FRO), International Seaways (INSW), DHT Holdings (DHT), Nordic American Tankers (NAT), Teekay Tankers (TNK), Overseas Shipholding Group (OSG), Tsakos Energy Navigation (TNP), Dorian LPG (LPG), Flex LNG (FLNG), Golar LNG (GLNG), Capital Product Partners (CPLP), ZIM Integrated Shipping Services (ZIM), Matson (MATX), Costamare (CMRE), and Kirby Corporation (KEX).

While some—such as Matson and OSG—are purely American companies, many others are controlled by Greek, Norwegian, or Israeli shipowners and operate large, internationally financed fleets. Collectively, these U.S.-listed firms control or operate thousands of vessels across all major sectors.

U.S. financial institutions, including Citigroup, J.P. Morgan, Oaktree Capital, and BlackRock, also manage or invest in significant port and fleet assets through leasing or capital investment structures.

If China adopts an operational definition of “operator” similar to that used in the U.S. Section 301 framework, the scope could expand even further. Many non-U.S.-flagged or non-U.S.-built vessels chartered on voyage, time, or bareboat terms by U.S. companies would likely fall within this category.

In addition to the listed shipping firms, major energy companies such as ExxonMobil, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips, as well as commodity traders like Cargill, ADM, and Bunge, operate substantial chartered fleets. Cargill Ocean Transportation, for example, manages a charter fleet exceeding 650 vessels worldwide.

TradeWinds data show that in most publicly listed shipping companies, U.S. investors hold more than 25 percent of equity, surpassing the ownership threshold defined under China's forthcoming measure.

Given that China is the world’s largest manufacturing and trading nation—and home to the busiest port network—virtually every major vessel type must regularly call at Chinese ports. This means the potential reach of the "Special Port Fee" could extend far beyond what headline figures on U.S.-flag tonnage might suggest.

Compared with the U.S. regime, China’s forthcoming measure could affect a broader and more diverse range of shipowners. Some external commentators have argued that China "has no meaningful card to play" or that the measure is "not truly reciprocal," but such assessments appear to underestimate both China's market leverage and its regulatory sophistication.

In reality, China is the world's largest manufacturer, top exporter, and a critical hub of global shipping demand. Almost all major ocean carriers, operators, and charterers—regardless of nationality—depend on access to Chinese ports. As such, any institutional adjustment introduced by China carries significant global implications.

China’s Position: Rational Counteraction, Stability Through Dialogue

As previously discussed, China's response represents reciprocal counteraction tempered by restraint. Facing what it views as a politicized and discriminatory Section 301 measure, China has chosen to respond with law, not retaliation, reflecting both governance maturity and strategic confidence.

The "Special Port Fee" is not an emotional reaction but a structured, rule-based response. From its timeline and fee schedule to its eligibility criteria and review cycle, the measure is designed with symmetry and transparency, signaling both a firm rejection of unequal treatment and a willingness to maintain dialogue.

In a world of deeply interconnected supply chains, stability outweighs confrontation. The purpose of countermeasures is to uphold legality, not to escalate; restraint serves to preserve rationality, not to concede. By responding to rules with rules and balancing institutions with institutions, China seeks to promote a fair, cooperative, and rules-based maritime order.

This transcends a mere dispute over port fees—it signifies a broader rebalancing of fairness, governance, and influence in global maritime affairs. Through a policy of rational counteraction and stability-driven engagement, China aims to demonstrate the posture of a responsible maritime power: firm, composed, and predictable.

As a Ministry of Commerce spokesperson put it, the countermeasure "aims to safeguard fair competition in the international shipping and shipbuilding markets" and constitutes "a legitimate act of legitimate defensive measure." The spokesperson added that China hopes the United States "will reconsider, correct its mistake, and work toward constructive solutions through equal consultation and cooperation."

by Xinde Marine News Chen Yang

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Xinde Marine News.

Please Contact Us at:

media@xindemarine.com