A range of factors have helped Asia's supply chains weather the COVID-19 pandemic better than those in other parts of the world. But vigilance is needed to maintain these vital trade links.

The pandemic has created supply and demand mismatches and reallocated global demand from services to goods. As a result, supply disruptions have emerged alongside the global recovery.

Asia, however, has been less affected than other regions, as reflected by smaller increases in delivery times by suppliers in the manufacturing sector from February to April 2020. Delivery times have remained moderate since May 2020.

What's more, deliveries are now faster than they were on average globally from 2016 to 2021 in China, Indonesia, India and Thailand. In the Republic of Korea, the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia, delivery times are longer, but less than in the euro area, the United States and several other advanced economies.

There are at least three reasons why Asia's supply chains have not been disrupted to the same extent as elsewhere.

First, demand in Asia did not shift from services to goods as much as it did in the US. Services activity in the region continued to be hindered by COVID-19 mobility restrictions in 2021, but reduced spending on services did not boost purchases of goods as much as it did in the US and in some other advanced economies. This was partly because disposable income recovered more slowly in Asia's developing countries than it did in advanced economies, and because fiscal stimulus-especially direct cash transfers to households-was much larger in the US.

Second, the upstream position of some Asian economies protected them from supply-chain bottlenecks. Bottlenecks at any point along a value chain can affect downstream industries. Upstream industries are thus somewhat more sheltered from disruptions. This includes the manufacturing of inputs for electronics, which is the backbone industry for several Asian economies.

Third, the region has also been less affected by rising shipping costs. The cost of shipping a container from Bangkok to main ports in Asia remained about 2.5 times above pre-pandemic levels for most of 2021. In contrast, increased demand for shipping from China to advanced economies inflated freight rates to up to 15 times their pre-pandemic levels in September last year.

While Asia has been relatively resilient, it has not, however, been completely immune to disruptions. Intra-Asia shipping costs have risen since mid-November, reaching 4.7 times the pre-pandemic levels at the end of February. This increase reflects port disruptions caused by outbreaks of the Omicron variant of the coronavirus and the reduced availability of containers and ships, as resources were reallocated to more lucrative routes.

Freight costs from China to Europe and the US rose again in the second half of February due to the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, but intra-Asia shipping costs did not budge.

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine will add to supply-chain disruptions, as both economies are key global suppliers of inputs used in manufacturing. Russia supplies 24 percent of global palladium exports and 23 percent of nickel exports, and neon gas from Ukraine accounts for up to 70 percent of global supply. These raw materials are key inputs for making catalytic converters, electric batteries and semiconductor chips. Restrictions in their supply would put further pressure on global automobile and electronics industries, including in Asia.

Higher shipping costs have pushed carriers to expand rail services via Russia-a route that is now at risk given the sanctions imposed on Russian Railways. The airspace ban above Russia and suspension of cargo bookings to and from most Black Sea ports further complicate existing transportation challenges.

So how much longer will these disruptions last?

In the short run, the lockdown in Shanghai is considerably delaying ship loading and offloading in the largest container port globally. As ships are lying idle, the delays reduce the capacity available for global shipping, push up freight costs and worsen supply chain disruptions.

In the middle run, shipping bottlenecks could be relieved by a decline in global demand for goods. This will happen when consumers rebalance their spending toward services, as economies continue to recover from the pandemic. But demand for goods may decline only gradually, and it could remain higher than pre-pandemic levels. Finally, replenishing inventories will add to the demand for final goods for some time after the consumption of goods has normalized.

If global demand for goods remains strong, relief to shipping will only come in 2023, as ships ordered last year start being delivered.

Global supply chains have been vital to ensuring the resilience of the global economy during the pandemic. Minimizing supply chain disruptions in difficult times is critical to withstand shocks. To alleviate these disruptions, governments can intensify efforts to cut unnecessary obstacles to trade and ramp up investments in digital infrastructure enabling seamless border crossing for goods.

Source: China Daily

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Xinde Marine News.

Please Contact Us at:

media@xindemarine.com

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

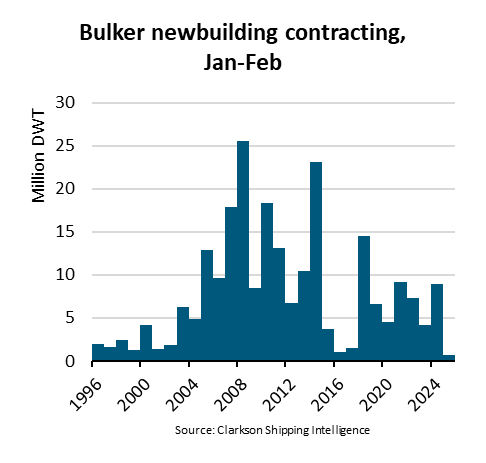

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi

BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar