Two nervous days have passed since the International Transport Workers Federation offered its blessing to thousands of seafarers, working beyond their original contracts, to cease work, with the cry “enough is enough!”

Thus far there has been no sign of industrial action by seafarers, and no indication that recalcitrant governments are relenting. Seemingly, both parties have reached an impasse but, with ominous signs that ship’s crews are reaching breaking point, mentally and physically, it is a stalemate waiting to be shattered.

One is forced to wonder if the jurisdictions that have locked out seafarers have thought through the logical consequences of their inaction. Should seafarers in significant numbers decide to follow the advice of their union(s) it would precipitate an unprecedented logistical crisis. Offending governments would be forced to reconsider their policies in relation to the landing and repatriation of crew in particular countries with large dependencies on imported consumer goods.

But any action taken in desperation by seafarers will inevitably end in manifold, and massive repercussions for themselves, their employers and society at large.

A quick call to a leading maritime lawyer, required, on the hoof, to come up with a few such repercussions yielded these responses:

The effect between the employer and the seafarer: Each of the crew contracts is effectively negotiated by the national ITF branch on a collective basis. As such, they will be subject to the law of the jurisdiction where the seafarer has signed on. This means, from an employment perspective, the question as to whether shipowners can force seafarers to extend contracts will be subject to the law of Philippines, India, China, Ukraine or whatever law is applicable to the crew contract. This is of course will be considered in the light of any obligations set out about extensions of contracts in relevant local legislation and flag state regulations.

The ITF had allowed 1 month extensions. That period has now expired.

As far as the charterer is concerned, it will likely be an offhire event if the crew stops work, being a “deficiency of men”. Depending on the charter party it is possible that force majeure or infectious diseases provisions may militate against that. Contractual carriers will continue to have obligations to cargo interests to carry the cargoes so there will be liabilities arising there also.

Turning to safety considerations a disastrous scenario emerges: Should crew members stop work the Master will continue to have an obligation at common law to ensure the safety of the vessel. Added to this are the obligations under the MLC in respect of safe manning.

It is not clear whether the refusal to work, would be refusal completely (including ensuring the safety of the ships) or just refusal to follow the commercial orders of the charterers/owners. But should they choose to take the second option, at this point the question of mutiny may arise. There is a US case from the 1940s (Southern Steamship Co v National Labor Relations Board) which held that a strike by seafarers to try to force the recognition of a labour union was a mutiny!

When industry organizations such as the Hong Kong Shipowners Association and the Hong Kong Liner Shipping Association meet with an enlightened government, progress can be made as evidenced by the 8 June decision by the Hong Kong Authorities to drop the 14-day quarantine requirement for seafarers of all nationalities together with an efficient and safe way to facilitate the joining of vessels and repatriation. Similar regimes have also been introduced by other jurisdictions such as Singapore and Canada.

It is to be hoped that the mere threat of a global logistics collapse will bring governments to their senses.

Source:

hongkongmaritimehub

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Xinde Marine News.

Please Contact Us at:

media@xindemarine.com

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

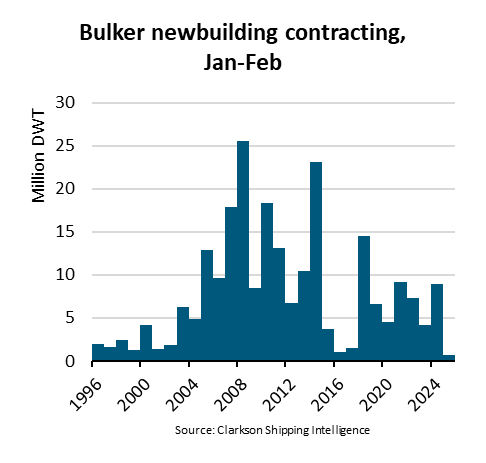

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi

BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar