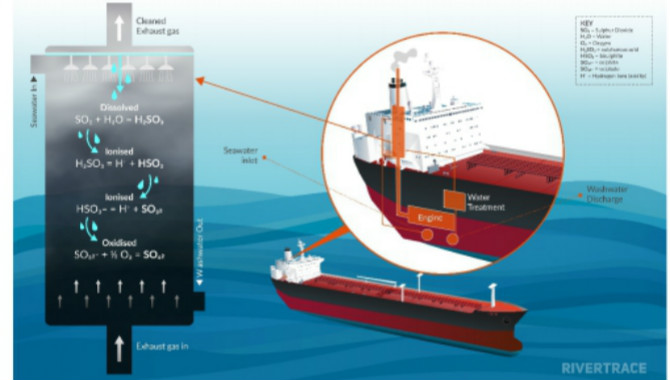

Image caption: Rivertrace’s SMART ESM (Exhaust Scrubber Washwater Monitor) fully compliant with MEPC 259(68).

The Global Sulphur Cap is just around the corner, but of course we all know that. Talk of this hard-hitting, change-inducing regulation has dominated industry airwaves since the culmination of more than thirty years of swirling debate at the IMO came down to the decision that bunker fuel sulphur content had to be capped at 0.5% to protect the planet.

IMO set a definitive entry into force date of January 1, 2020 and stuck to it, resisting demands for delay from those concerned with bunkering infrastructure deficiencies, fuel shortages and fears over emissions abatement technology use.

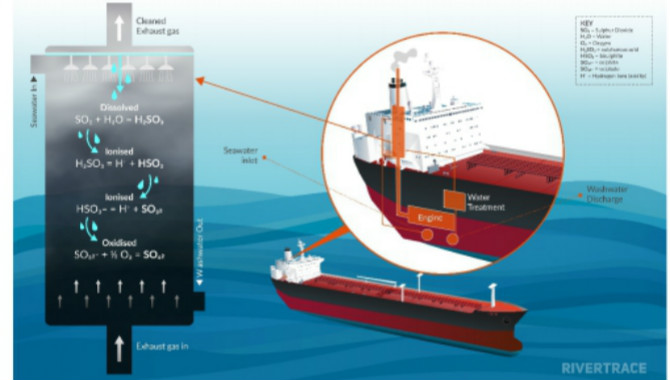

Ship owners were granted two options for compliance: bunkering low sulphur fuel oil (LSFO) or install an exhaust gas cleaning system, more commonly known as a scrubber, and continue to bunker high sulphur heavy fuel oil (HFO). Seeing as HFO has reigned as the king of marine fuels since the middle of the last Century, scrubbers offered ship owners a way of clinging on their favoured fuel and steering clear of inflated low sulphur fuel prices. However, even with that IMO approved option is on the table, the ‘to scrub or not to scrub’ debate rages on.

What should be a simple matter of choice between available compliance options has been made unnecessarily complex by increasingly acrimonious, and sometimes ill-informed arguments over the validity of the available choices. Scrubbers have come under repeated attack and ongoing arguments have stifled the uptake of technology, hindering its acceptance by the industry.

For scrubber pessimists, washwater discharged to the sea from open-loop scrubbers is a huge issue. Many argue that this represents the transfer of pollutants to the marine environment. The lack of trust in washwater discharge composition has led to a series of countries and coastal states have banned the use of open loop scrubbers at ports located in their waters including China, Singapore (as of 2020), Fujairah and California, to name only a few.

On the other hand, certain nations have, since conducting careful analysis of scientific literature and extensive testing of washwater, decided to not ban open loop scrubber operation in their waters. Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, for example, has concluded that no short-term or long-term effects on marine organisms were likely to be caused by the use of this technology.

Being able to prove that washwater quality is constantly monitored and shown to meet appropriate standards is essential for scrubber technology acceptance by the industry. However, herein lies a problem. Although each scrubber system manufactured must be equipped with a monitoring system so that water quality on the inlet and outlet can be monitored, their use is not a mandatory requirement. The rules for scrubbers and their washwater discharge and monitoring criteria are only IMO guidelines at this time. Guidelines put in place before the use of scrubbing technology outside of ECAs was obligatory if low sulphur fuel isn’t bunkered.

While nothing about IMO decisions is ever certain, the fact that scrubber washwater remains to be the only discharge of its type not subject to the same standards as discharges from other shipboard systems will almost inevitably lead the requirement of mandatory monitoring. Because of IMO procedures it is too late for that to happen before 1 January 2020, but it may come within 2020 or 2021.

If this were to happen, monitoring equipment would need to meet exacting performance standards, which has not been a requirement previously. Scrubber manufacturers would need to use multiple devices to measure all the required parameters or integrate a single monitor that has multiple parameters.

Ahead of anticipated mandated monitoring requirements, it is vitally important that ship owners select a scrubber equipped with robust monitoring equipment from a proven independent supplier rather than one from a lesser known source. Any future failure in monitoring under anticipated regulatory rule could mean that the scrubber operation may need to be stopped and a much more expensive compliant fuel be used temporarily.

With the majority of scrubbers being manufactured and installed in Asia, 5000 systems installed at Asian shipyards to-date representing 43% of scrubbers ordered and installed (Clarkson’s Research Services World Fleet Register Listing data August 2019), Rivertrace has risen through the ranks to become the number one scrubber washwater monitoring equipment supplier in the region. Our Smart ESM monitoring system was developed specifically for use in marine scrubbers, rather than being adapted from land-based applications, when used, can suffer problems associated with not being robust enough for marine environments.

Mandated scrubber washwater monitoring requirements should not be feared, they may be the best option to ensure that all scrubber variants remain permitted for use in the future and on the widest possible scale. However, the use of robust monitoring technology that provides reliable information to ensure compliance with the worldwide fuel sulphur content limits is a need to have, rather than a nice to have.

Image caption: Infographic showing the chemistry of washwater

免责声明:本文仅代表作者个人观点,与信德海事网无关。其原创性以及文中陈述文字内容和图片未经本站证实,对本文以及其中全部或者部分内容文字、图片的真实性、完整性、及时性本站不作任何保证或承诺,请读者仅作参考,并请自行核实相关内容。

投稿或联系信德海事:

media@xindemarine.com

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

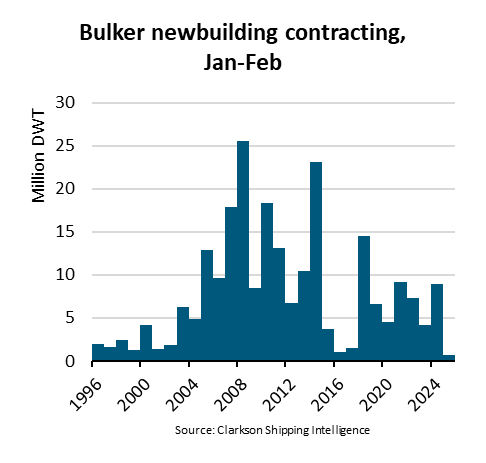

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi

BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar