Presentations addressing the issue of seafarers’ welfare, delivered at the Duty of Care Conference in Hong Kong this week, offered reasons for despair but also for hope.

First the bad news. Suicide rates among seafarers suffering from poor mental health have more than tripled since 2014 according to figures from the UK P&I Club’s internal claims system. Furthermore, in 2018, the International Seafarers Welfare and Assistance Network dealt with 3,500 cases of mental health issues involving some 8,700 seafarers.

But fears of a mental health epidemic at sea might be overstating the case. According to research undertaken by International SOS of medical cases registered across 1,000 vessels in most classes of commercial fleets, and seafarers of 50 nationalities, mental illness barely registers compared to dermatological cases at 14% and accident/injury at 13% of cases. Gastrointestinal and dental both accounted for 11% of cases registered. Although psychiatric/psychological cases register a very small percentage of recognised cases they have been increasing over the period 2016-2018.

From a P&I perspective, provided by head of claims and deputy head of Skuld (Far East), Nicola Mason, crew claims accounted for a considerable portion (29%) of all claims paid out in 2016/17. There are interesting variations on different classes of vessels. On container vessels crew claims amounted to 22% of all P&I claims; 34% on tankers, and 41% on bulkers.

The most common illnesses that resulted in a claim were heart disease and associated illnesses such as stroke and hypertension at 26% of all crew illnesses. By contrast mental illness accounted for 6% of payable claims. Crew claims overall resulted in four crew files being opened every day over the five-year period analysed.

However, it is strongly believed that mental health issues can more easily go undetected than say a toothache or a heart attack. Unfortunately such mental conditions may well be contributory factors to the more noticeable physical conditions without anybody knowing.

John Wood, manning and marine manager at China LNG Shipping (International) identified stress and its symptoms as well as the more elusive, lesser known “burn out”. Stress is characterised by over-engagement, overactive emotions, hyperactivity and consequent loss of energy, anxiety disorders, with the primary damage being physical. On the other hand, burnout has symptoms less likely to be picked up by outsiders and includes disengagement, blunted emotions, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, loss of motivation and depression; the primary damage is characterised as emotional or mental.

Identifying the presence of mental issues among crew is dependent on close attention, particularly from the senior officers, says Mr Wood. “It’s about connecting with your team.”

Mr Wood insists that such attention begins from the moment crew join ship:

“We all know before being assigned duties onboard all persons employed or engaged on a ship must be familiar with the ship, the equipment and systems onboard. But is there a greater need for seafarers to familiarise themselves with their fellow shipmates.?”

“After all, they’re relying on each other in many aspects of their daily work and in the unlikely event of an emergency.”

Mr Wood calls upon senior officers to maintain a physical presence in the workplace and during social interactions after working hours to help identify changes in morale and team dynamics, which are key signals in identifying mental health issues. While this approach may appear to be a little ad hoc. CLSICO has been ahead of the game, training office and sea staff through relevant courses to raise awareness of symptoms of mental distress before 2016 amendments to the Maritime Labour Convention required governments and ship owners to adopt measures to better protect seafarers against shipboard harassment and bullying.

Captain Hamanshu Chopra, QHSE manager at Anglo-Eastern Ship Management outlined the emotional challenges at sea, primarily, job stress, family pressure, anxiety, social isolation, and disturbed sleep, to name but a few. Multiply the possibility of such symptoms occurring by 27,000 (Anglo Eastern’s crew complement) and there is clearly the need for a scalable strategy.

With the majority of AE’s seafarers falling into the millennial demographic, the company has embraced the digital approach most fitted to that generation. The adoption of an Anglo -Eastern Mariner App, crew can stay connected whilst at home and at sea while keeping a record in-hand of all the most important aspects of their role within the company.

Individual health care is also managed digitally providing continuous medical records and always on health monitoring. Digital publications offering advice on maintaining good health are frequently released and updated. The app also allows for crew members to share their stories across the fleet and to loved ones at home.

At a more serious level AE also issues suicide prevention guidelines and access to online counselling courtesy of the Seafarers Hospital Society’s Big White Wall.

All new recruits are subject to a strict pre-joining medical screening and psychometric testing. Having crossed that hurdle cadets will be nurtured through new trainee monitoring, known at AE as the Buddy System.

For those that still fall victim to a mental disturbance a team of psychologist are in hand within the company.

While it is true that seafarers often face unique challenges. It is clear that the better shipping and shipmanagement companies are rising to the those challenges and one must be careful not to get caught up in a moral panic. In an eloquent article provide to the Global Maritime Forum by AE’s chief executive, Bjorn Hojgaard insists that the seafarer is not to be pitied.

“Yes, seafaring is not for the faint-hearted and the job really does entail long periods away from home, with the sacrifices and pains that come with that. On the margin, it can also be a dramatic, headline-attracting experience, but for the vast majority it is a job, different from other professions and often a vocation, but a job nevertheless. It is a chance to work in a complex environment and in an exciting industry that is central to global commerce,” Mr Hojgaard wrote.

“Onboard a ship every person counts, and the variability of the days makes life aboard no dull matter. Wages on the whole are decent, and onboard a ship a seafarer is an independent, decision-making unit. As part of a large supply chain the seafarer’s ability to take control over or influence one’s own work is unrivalled. It’s a free life, where the periods of hard work and confinement are rewarded with extended time off after a tour of duty and financial freedom to pursue dreams that may otherwise not have been possible.”

Few of us should doubt it.

The Duty of Care Conference was organized by International SOS Foundation and the Employers Federation of Hong Kong

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

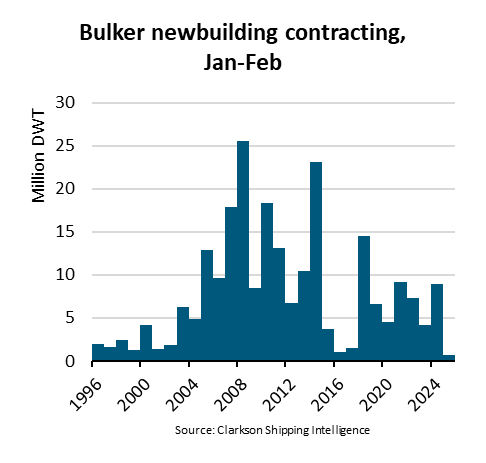

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi

BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar