Many speculate the ban is a direct result of political tensions between the two countries. Tensions first surfaced in 2017 when Australia accused Beijing of meddling in its domestic affairs. In August 2018, Australia refused to use equipment from Huawei and ZTE to develop its 5G network, while it recently revoked a Chinese billionaire’s permanent residency in fear that he was interfering with the country’s political affairs. China is believed to use its advantageous position as a top importer of Australian coal to advance its foreign policy agenda. However, government officials from both countries have dismissed the idea that political motives lie behind the ban. According to the Chinese foreign ministry, the ban was imposed not only to protect Chinese importers and support domestic prices, but also for environmental reasons.

At the face of it, the ban looks substantial. However, looking at it closely, it should not have a material impact on neither of the countries involved.

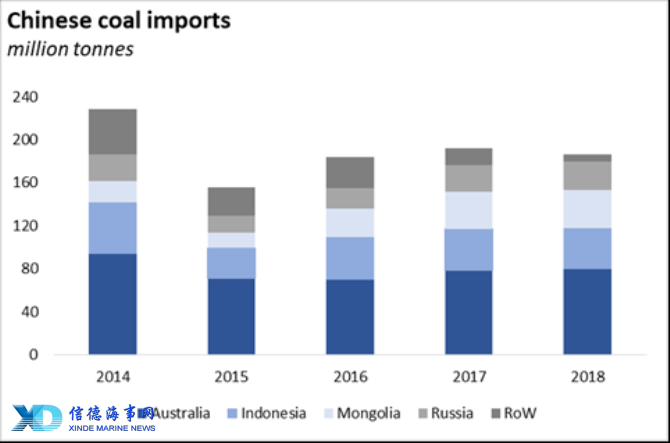

The ports in question only accounted for about 7% of total Chinese imports in 2018 according to government data. We do not believe that China will escalate the current situation. Firstly, the country is dependent on high-quality Australian coal; Australia is China’s number one source of coal, exporting 80.4 million tonnes in 2018 or 43% of the total imported. If China wished to replace Australian supplies in the short-term, it would have to ramp up imports from major exporters like Indonesia and Russia, although their coals are of lower quality compared to Australian ones, resulting in lower efficiency and higher emissions. Mongolia is another important supplier of coal to China, but could not be a short-term game changer due to logistical issues. Moreover, China will probably not risk an increase in coal prices, especially at a time when steel mill margins are weak due to high iron ore but weak steel prices.

As for the reduced quotas, they seem to be in line with the Chinese government’s intention to slow down imports following a strong January and in order to avoid another strict halt in imports similar to the one imposed at the end of last year.

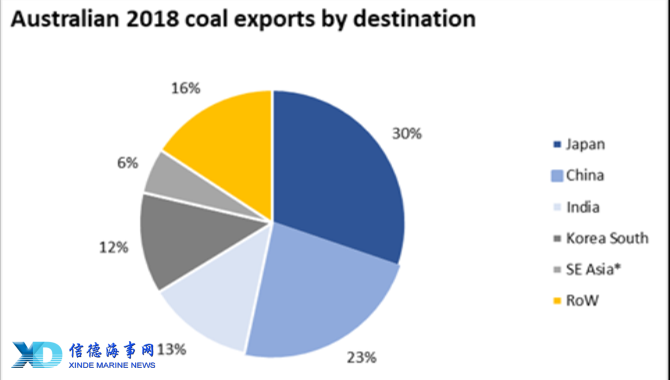

As for Australia, the loss of exports to China is not catastrophic. Japan remains number one destination for its coal despite a marginal fall in volumes since 2016. The situation is similar in South Korea. Even so, the slight decline in exports to Japan and South Korea is more than offset by a strong rise in exports to other SE Asian countries*, which surged 27.5% or by 4.6 million tonnes in 2018.

Should the ban be long-term or expanded to other ports, however, the global coal trades could see significant changes. Firstly, Chinese domestic coal prices would probably spike. By contrast, Australian prices would drop further as excess coal would have to be distributed to other markets; a welcome outcome for steel makers in Asia and Europe as costs would drop as well. SE Asian exports would also benefit from taking up Australia’s share in the Chinese market.

It remains to be seen how the situation will evolve but we believe that this will be a temporary disruption with limited impact on coal trades.

Source:Arrow

Please Contact Us at:

admin@xindemarine.com

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

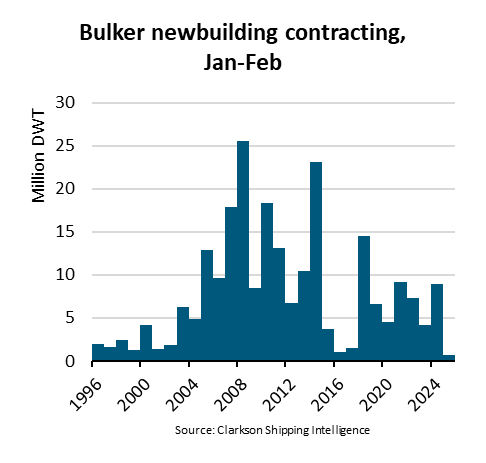

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi

BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar