Being a sailor was a valued job back then."

Hard work, poor pay

Those days are long gone. Now, many merchant seamen regard the job as a temporary berth.

"When I get married, I won't work as a sailor," said Wu Chao, an able seaman on the MV Tianbaohe. "It's not possible to do this job for one's whole life."

The 28-year-old from Yancheng, Jiangsu province, joined Cosco's merchant fleet in 2014 after spending five years in the People's Liberation Army Navy, during which time he took part in escort duties in the pirate-plagued waters off the coast of Somalia.

Crew members usually spend seven to nine months at sea during each voyage. After, they return to China for a vacation that should last three to five months, but is often shorter, depending on the availability of crew members and Cosco's schedule.

While officers stay with the same ship for long periods, able seamen and lower ranks are often assigned to new vessels on each voyage.

The rigid schedule means the sailors spend most of the year at sea, which can result in tensions.

"I was in a relationship for six years and we were going to get married, but we broke up when I became a sailor four years ago," Wu said. "My girlfriend's parents thought I wouldn't be able to take good care of her."

Moreover, only some senior crew members are paid while on leave, but the lower ranks receive nothing.

As an ordinary crewman, Wu earns 6,600 yuan ($1,000) a month at sea. "The money is acceptable aboard ship, but it's not nearly enough at home," he said.

The MV Tianbaohe has 10 senior crew members-including Captain Huang, who earns about 17,000 yuan a month, while the other officers make an average of 10,727 yuan-and 12 ordinary sailors, including able seamen and motormen (mechanics), who earn 6,687 yuan.

"Our incomes are no higher than on land now, such as those for couriers and food delivery riders," Huang said.

Stress and safety

Every day, Wu is required to spend two four-hour watches, one in the morning one at night, assisting the third officer on the bridge in steering the ship, monitoring radar screens and looking out for other vessels. The other officers and crew take the helm at other times.

Life on the bridge is stressful, but the engine room-where the main engine and boilers are located-is far harsher physically as a result of the deafening noise, high temperatures and the overwhelming stench of diesel oil. Despite the heat, the engineers and motormen who maintain the equipment must wear earplugs and protective uniforms.

"If the engine alarm system sounds, we must remain on 24-hour standby to check and maintain the facilities at short notice," said Zhu Wenming, the chief engineer. "Otherwise, there could be operational problems that could threaten the ship's safety."

At these times, Zhu sleeps on a sofa rather than in his bunk to ensure he won't sleep too soundly and fail to hear if an alarm sounds.

When things are running smoothly, the biggest danger the sailors face is boredom, because the work is repetitive and they rarely find a mobile phone signal, meaning they cannot contact their families.

"Life at sea is really dull," said Zhu Mingliang, 31, who was a sailor for eight years.

"I often asked myself why I became a sailor. Having no phone signal for days means sailors lose contact with society and can't connect with their families," he said. "When I came home last year, I tried to hug my little son, but he pushed me away. I felt guilty at being unable to look after my home."

Zhu earned 7,000 yuan a month, which wasn't enough to support his family, so he quit and opened a fruit store in his hometown.

Tao Jie, 29, a motorman on the MV Tianbaohe, has been single for six years. His parents have been urging him to find a new job for about two years, but he is reluctant.

"I've been a sailor for many years, and I'm not capable of doing any other work, so I could easily find myself earning far less," he said, adding that many of his shipmates share his opinion.

Although he understood their concerns, Zhu said the sailors were naive. "You won't know the result if you don't try to change. Of course changing jobs can be risky, but I was willing to face that," he said.

Recruitment difficulties

Ministry of Transport figures show that there were 709,000 merchant seamen in China last year, accounting for one-third of the global total.

When Nantong University in Jiangsu province conducted a survey of more than 9,000 sailors in 12 provinces and regions in 2015 and 16, more than 80 percent of respondents said the job was unattractive, according to China Ship News. The paper also said that only 30 percent of navigation graduates were willing to join the merchant fleet.

"It has been increasingly difficult to recruit seamen since the second half of 2016," said Hu Xiaohong, deputy director of Party and Mass Affairs at Shanghai Ocean Shipping Co, which manages Cosco's container fleet.

He said that before 2016 the company usually recruited about 180 trainee seamen in the first half of every year, but in the past six months it has hired fewer than 30.

That decline has also been noted at the Qingdao Ocean Shipping Mariners College in Shandong province. Yi Shanqiang, a teacher in the Navigation Department, said that in 2014 the department held 12 classes for students from Shandong, but in the past two years it has only held seven.

Both Hu and Yi said the lack of recruits was the result of the low status of sailors and poor wages, while Huang, the captain, felt it was due to insufficient government support.

Market conditions

However, Zhang Duo, a professor of seaman rights at the college, said sailors' incomes are mainly decided by shipping companies and market conditions, so the government's role is limited.

"Seamen's incomes vary according to the company they work for. The international shipping market has slumped since the 2008 financial crisis, resulting in less cargo and fewer orders, so ship owners are earning less," he said. "Naturally they are trying to reduce employment costs by spending less on salaries."

Hu said his company needs to find a balance between reducing labor costs and retaining talent, even though that's a contradiction in itself.

Li Shixin, deputy director of the Maritime Safety Administration at the Ministry of Transport, said the overall income of seamen hasn't fallen in real terms.

"Actually, it has just fallen relatively compared with rising prices and higher salaries in other jobs," he said. "But we have been studying how to improve the seamen's situation."

In 2016, the Chinese Seamen and Construction Workers' Union established a standard monthly base salary, which has risen every year after negotiations with the China Shipowners' Association. This year, it rose to $632, and for the first time exceeded the $614 base level set by the International Labor Organization.

For the past three years, the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference has heard a proposal that oceangoing seamen should be exempt from income tax.

The proposal has not been adopted, and Li said tax reform is a complex issue which will require the joint efforts of governments, the shipping industry, companies and other sections of society.

However, those efforts will probably have to be made quickly if the industry is to avoid a massive shortfall of talent.

"People always say you should love your job, but I only do this to make a living," Wu Chao said.

"I will probably quit in three or five years, because I will have to start a family by then."

Sources:chinadaily

Please Contact Us at:

admin@xindemarine.com

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

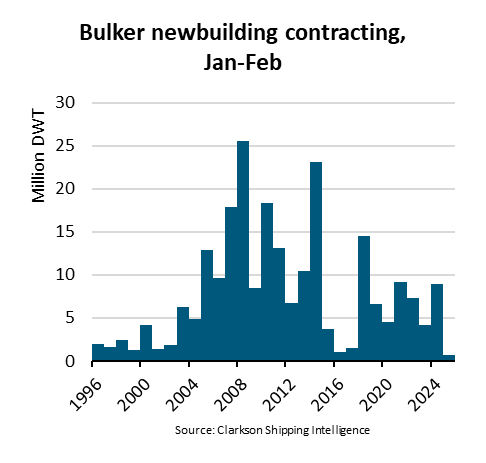

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi

BIMCO Shipping Number of the Week: Bulker newbuildi  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar  Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar

Ningbo Containerized Freight Index Weekly Commentar